Engineering as Art

While I’m in college, it feels as if everything I do is in pursuit of the “craft” of engineering. I rarely, if ever, take the time to connect my creative and analytical brains. Engineering is art, I’m sure of that much. But in order to back up my claim I’ve got to give some good examples. These are my personal experiences in class and on co-op, offering my view into the intersection of creativity and engineering.

Six months and at least a thousand hours on the clock, and all it took was one line of code. A bug I’d been chasing for at least two of those months was finally done. I sat back in my chair and laughed at the absurdity of it all. When I was asked about this experience in a job interview months later, I struggled to explain why it was the most important bullet on my resume. At this moment I began to realize that engineering is far more than a technical discipline – it is an art form.

A classic example to the art in troubleshooting is Charles Steinmetz, an electrical engineer from Schenectady. In the early 1900s, Ford motors could not get their giant brand-new generator to produce consistent power. After months of unsuccesful troubleshooting, they hired Steinmetz. He came, spent two days listening to the generator, and made a single pencil park on the problem. They replaced the part and the generator worked perfectly. A week later, a bill for $10,000 showed up on Ford’s desk. Henry Ford thought this was absurd and asked for an itemized invoice. Steinmetz replied with the amounts “Making chalk mark on generator – $1. Knowing where to make mark – $9,999.”

Steinmetz with Einstein at the Marconi Station. Image courety of wikimedia.

Steinmetz with Einstein at the Marconi Station. Image courety of wikimedia.

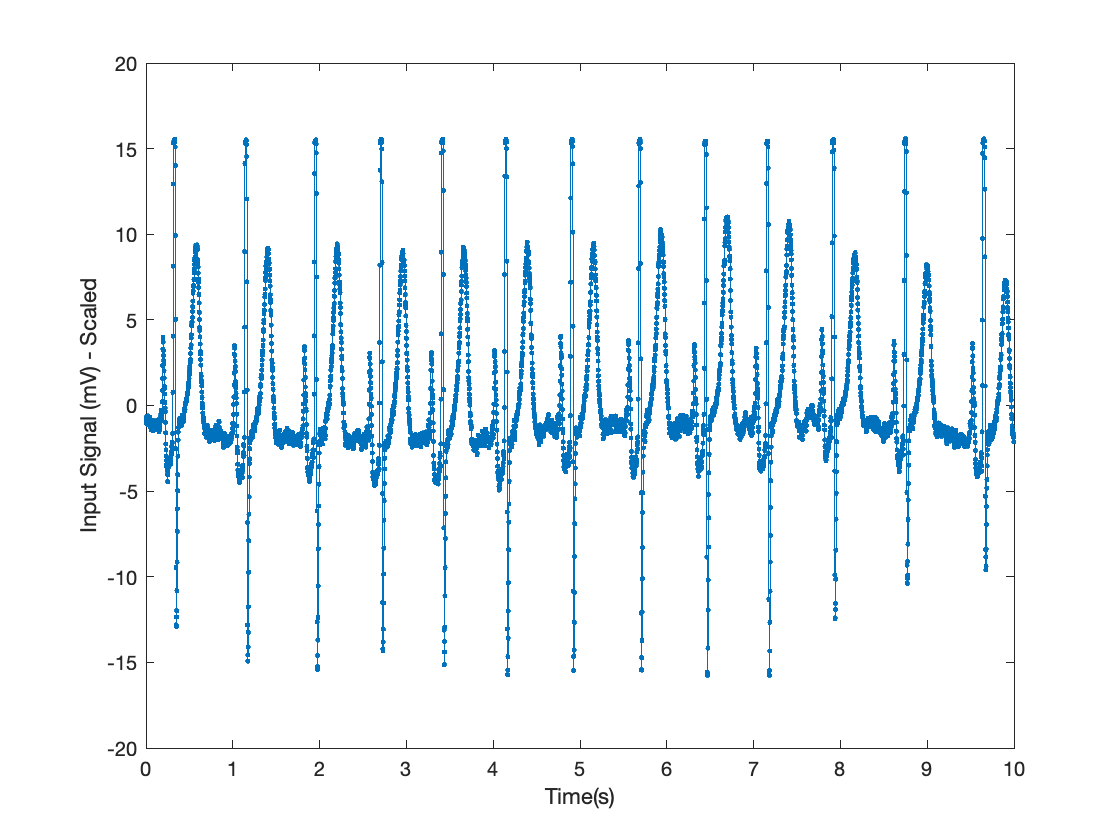

In class, it feels as if repetition is the only way to learn. But repetition frequently equals getting bored, and the majority of my circuits and signals course was just that. To my surprise, the final project changed that assumption for the better. Our final project was to build a working Electrocardiogram (EKG). I had no idea that our own bodies generated electrical impulses, let alone ones we could read with simple circuitry. I learned how to build and test analog filters from scratch, carefully building intricate circuits on the provided breadboards. By the final class, my lab partner and I had managed to assemble all the filtering components into one circuit and hook it to a digital acquisition system for analysis. I hooked the leads to my lab partner’s chest and turned the system on. To my utter disbelief, we got a perfect reading. We had been working continuously for the past three weeks on methods of digital filtering, as we were told that the analog signal our circuit produced would be too noisy. Instead, we needed no digital filtering and had a perfect signal on the first try. That was a moment of artful bliss for me.

For me, the easiest example of engineering as art lies in the pen plotter, a robotic hand just as masterful as that of a painter. They’re incredibly simple devices that hold a pens and move in the X and Y axes. Through simple motion it can create unimaginable beauty. I often find myself writing algorithms for the plotter with the intention of not simulating them. This is because I crave the moment when I can run the code and let the robot take control of the pen, not a clue as to what will happen. I can sit for hours watching the plotter draw spirals, triangles, multi-faceted shapes, and more. This kind of engineering can be so spontaneous, almost a dance between code and creation. The result is art, no doubt, but the beginning is just lines of code on a screen.

As I write of these stories, I’m beginning to realize that engineering is more than practice but is in fact firmly art. Today more than ever before we are harnessing computers to do our work for us. While generative systems are capable of great things, the single broken line of code, the single white chalk mark, the single right antenna design, and the single perfect analog circuit cannot be done like a human can. I oft find myself echoing the sentiment that good engineering is indeed an art form, requiring not only technical skill but also a keen sense of intuition and innovation.

Author’s note: This post was written as part of a project for ENGW3302 - Advanced Writing in the Technical Professions. Thank you to Prof. Gilreath for a great project idea and a lovely class.